READ THE PODCAST

Annoushka Ducas:

I'm Annoushka Ducas and welcome back to My Life in Seven Charms. For me, there are so few things which can evoke a memory like a tiny detailed

In this new series, I'll be meeting seven extraordinary women and hearing their stories through this very special 18-karat gold biography. In this episode, we'll be meeting best-selling writer, Jung Chang.

Jung Chang:

I always loved writing when I was a child, but when I was growing up in China in the 1950s, '60s and '70s, it was impossible even to dream of becoming a writer. And then in 1988, my mother came to stay with me. For the first time, she told me the stories of her life and stories of my grandmother, her relationship with my father, and after she left, I wrote Wild Swans and I became a writer.

Annoushka Ducas:

Writer, historian, educator and someone who shone a light for millions of people around the world onto the recent history of China, Jung was born 14 years before the Chinese culture revolution began. Her family experiencing hardships that you and I could only imagine. Her memoir, Wild Swans, telling the story of growing up under Mao's regime went on to sell more than 13 million copies worldwide yet, her success has come at personal cost. Her books banned in her homeland to which she is unable to return, separating Jung from her beloved mother. I'm truly humbled to hear her story firsthand.

Annoushka Ducas:

I'm delighted to welcome the truly inspirational Jung Chang to My Life in Seven Charms. Thank you so much.

Jung Chang:

Well, thank you. Thank you for inviting me and thank you for making this wonderful things out of the objects each of which reminds me of a period of my life and very close to my heart.

Annoushka Ducas:

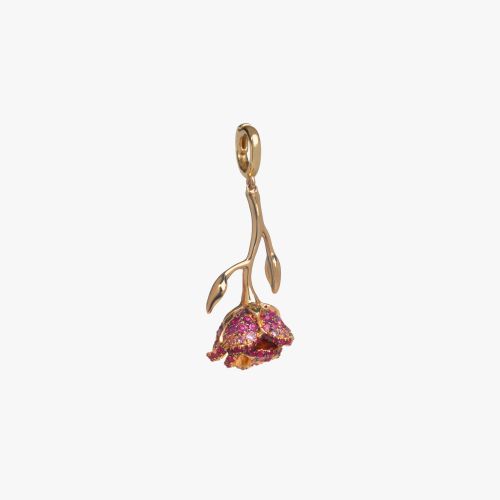

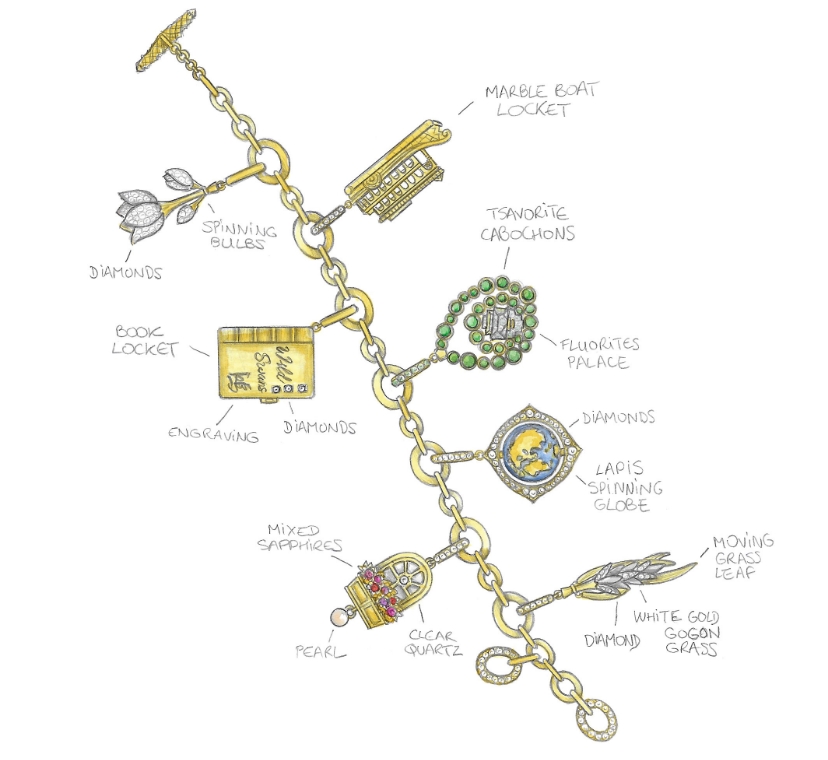

I'm so pleased that you were excited by the drawing. Why don't we start with your first

I haven't done it in a particular order but I thought your first

was a magnolia, the magnolia flowers. And when I asked you, you were very specific about this

because you said that it got to be closed magnolia flowers, and so I've drawn it. I see it as the stem being

and the petals are made in

with white diamond pavé, so tiny little

all over it. And inside where you can't see it from the drawing, but there just be two or three little tiny yellow stamens which the magnolia has but the whole thing will move as it was on a tree. Tell me a little bit about why you chose this

Jung Chang:

Well, magnolia is connected with my childhood memories of my grandmother. My grandmother really basically brought us up because my parents were always busy working, and she always had a magnolia, unopened magnolia in her hair.

Annoushka Ducas:

Oh, lovely.

Jung Chang:

And in those years, in the late 1950s and 1960s, China was a very regimented, puritanical society and everybody was wearing this Mao uniform, this drab clothe. Nobody wore any flowers and I noticed that people were looking at her and she was a little self-conscious but she was also a very beautiful woman. And then I would remember that we came back home and my grandmother would take off her magnolia flower and then put it in the bowl of water to refresh it. And then, she will to soak her feet, her crushed and bound feet into a big bowl of hot water, and you know this old Chinese tradition that tortured women for thousand years?

Annoushka Ducas:

Yeah.

Jung Chang:

My grandmother was one of the last generation to have her feet crushed and bound, and she said, "People say you will get over the pain, you will never get over the pain." And so, my image of my grandmother was this mixture of beauty and pain.

Annoushka Ducas:

It's so hard to conceive that now in our day, to conceive that that actually really happened. It's just extraordinary. I mean, I love the idea of her wearing these flowers in her hair. Do you think that was a kind of act of defiance on her part? What do you think made her do that?

Jung Chang:

Yeah. It was her way of being defiant. She was deeply unhappy about what was happening around us, in this great famine in the early 1960s. I remember when I was a child, I heard her talking about it and expressing loathing for what was happening because she had a best friend who was actually the maid of our family. The maid's family was in the countryside and they all died of starvation except her. I remember hearing things from her that was completely different from the party line which I heard in the school.

Jung Chang:

The other thing about my grandmother, she was a concubine. When she was 15 she was basically given by her father to this warlord general to be his concubine. A concubine is a victim of that old society because my grandmother was married to my grandfather for six days and he left for six years because he had other concubines dotted around China and he only visited them when he was next in town. And the rest of the time, my grandmother lived as a virtual prisoner in the house he bought for her. My mother was her only daughter so my mother was like my grandmother's purpose in life. When my mother was one years old, my mother was taken away from her because by tradition the blood descendant had to be raised by the proper wife and not by a concubine. So she escaped with my daughter with the help of another sympathetic concubine and all this was on her bound feet, so that was really quite extraordinary episode in their life.

Annoushka Ducas:

Bravery. Huge bravery.

Jung Chang:

But I also remember my grandmother, she really loved beautiful things. I mean, the warlord general, her husband gave her lots of jewelry because he believed, as lots of men believed in those days, jewelries were the key to a woman's heart. And so when he went away...

Annoushka Ducas:

Still is, isn't it?

Jung Chang:

[inaudible 00:08:12] and he gave her lots of jewelry, and these jewelries sustained her not by sentimental value but the values. I mean, my grandmother lived on these things when he didn't come back. And she kept some, she kept a jade bracelet and a ring and those were not the jewelry given to her by the warlord general, but by her second husband who was a doctor. Because after my grandmother fled from the general's mansion with my mother, she went back to Manchuria which was her home and there, she fell in love with a elderly doctor and they wanted to get married. But the doctor was many years older and he had children, grandchildren, even a great grandson and his family were against the marriage. And the doctor's eldest son was so furious, he shot himself in protest. He didn't mean to die but he died. And so it was impossible to live in this big family so my grandmother, my mother and Dr. Xia, my step grandfather, left and started their life again in another city.

Jung Chang:

So when I was growing up, my grandmother was always saying to us, "If you have love, even plain cold water is sweet."

Annoushka Ducas:

Do you still have those pieces of jewelry?

Jung Chang:

Well, in fact, they were confiscated by the Red Guards, but after the culture revolution, they were returned to us. In fact, I have a bracelet and a ring here in London. And so I was very, very close to my grandmother and her death was this tremendous painful spot in my heart.

Annoushka Ducas:

People say that one of the most wonderful things about jewelry is the story and the narrative that it holds. My goodness, that is quite a story.

Jung Chang:

Indeed.

Annoushka Ducas:

Your second

I love this, is the wild cogon grass that you described to me and each little leaf is individual and it moves. So the outer leaves I've done in white gold and then on the inside are these white seeds, again, all moving, made of

I mean, I think I'm right that this

was inspired by really beautiful memory of your mother and I'd love you to tell me more about that.

Jung Chang:

Yes. Well, actually, you're also absolutely right. It's the swaying cogon grass that's stuck in my head. We have to start with the beginning of the culture revolution in 1966. My parents became victims of the culture revolution. My father was one of the few who stood up to Mao and protested the culture revolution. So as a result, he was arrested, tortured, driven insane, exiled to a camp and also, he died prematurely. My mother was under tremendous pressure to denounce my father but she refused. So as a result, she went through over a hundred of those ghastly denunciation meetings. She was made to kneel on broken glass, she was paraded in the streets where children spattered her and threw stones at her, and then in the end, she was exiled to a camp in Xichang where these white golden cogon grass grew in perfusion.

Jung Chang:

And at the beginning of 1970s, I went to the camp to visit my mother and so I went to see my mother, I had a basket over my shoulder and in the basket were foods where my siblings and I had to save to give our parents a treat because was my father was in another camp. He and my mother were actually quite close, the camps were quite close but between them were mountains and they were not allowed to see each other. And so, I went to see my mother first and then I was about to go and see my father. And the day I was about to leave was the Chinese New Year's day. So my mother was tremendously sad that on this day which was the day for family reunion, I had to leave and then we didn't know when we would see each other again but I had to leave. I had to leave for my father's camp because the driver of the truck I had hitched, hitchhiked promise to come on that day to pick me up because his truck was passing by that road.

Jung Chang:

So my mother walked with me to the roadside with the basket of food untouched. She insisted on me taking everything to my father. And so we walked to the roadside and we sat down to wait. It was very sunny and between the roadside where I was to be picked up by this truck driver, the white golden cogon grass were swaying all around us. And then, in the distance, we saw smoke coming out of the roof of my mother's camp and that was her camp cooking breakfast and on Chinese New Year's day they were having this thing call the tang yuan which was this round dumplings symbolizing family union. And so, when we're waiting for the driver, he didn't come for a long time and my mother was gripped by anxiety. She thought I missed this New Year breakfast and she insisted on going back to get some tang yuan for me.

Jung Chang:

And while she was gone, the truck came and I couldn't keep the driver waiting. So I climbed to the back of the truck and I then saw my mother coming, running towards me. The white golden cogon grass swaying around her and she was wearing a blue scarf that was also flying. But she was running because she saw me climbing onto the back but she was running in a careful way that showed me that she didn't want the soup with the dumplings to spill. Then I had to go and so I left and years later my mother told me that she saw me climbing onto the back of the truck and the tang yuan, the soup, the breakfast dropped from her hand but she still ran to the spot where we were waiting just to make sure it was me who climbed onto the truck.

Annoushka Ducas:

It must have been totally heartbreaking for both of you. And while she was in the camp, who was looking after you? Were you looking after yourselves?

Jung Chang:

Oh. Absolutely. Not only that we're looking after ourselves, we were also looking after our parents. I mean, when I was 16 the culture revolution started. My parents were being denounced, they were ill, they were beaten, basically I think I didn't have this teenager period. I was thrown from my childhood to straight teen to adulthood. And my father's ribs were broken and I remember my mother was kneeling on broken glass and my grandmother used a tweezer to pick out that fragments of the glass from my mother's knees and I was helping my grandmother acting like a nurse.

Annoushka Ducas:

Oh my god. Absolutely shocking. It wasn't really childhood. It was a total role reversal. And when did she come out of the camp, your mother?

Jung Chang:

She came out of the camp in the early 1970s because the political situation changed. People like my parents, their situations changed for the better and my mother was able to leave the camp and later my father as well.

Annoushka Ducas:

So they were reunited?

Jung Chang:

Yes. In 1973, they were reunited. Yes.

Annoushka Ducas:

Gosh. Well, that must have been an extraordinary moment for you as a family.

Jung Chang:

Yes. I remember when my father first came back being in the mountains for many years and in isolation, in very hostile environment, had to be subject to denunciations, made to do the heaviest job and I was also in my father's camp several times. Again, I traveled by myself to give him a part from helping him doing some work and physical labor and to give him some company because in those days, the love from your family was the thing that sustained you. And my father said, if it hadn't been for his family, he would have committed suicide long time ago.

Annoushka Ducas:

Okay. I mean, how incredibly strong you must have been. Your next

Jung Chang:

It's absolutely wonderful. And of course, the Chinese character on the cover of Wild Swans means wild swans. Dr. Xia, my step grandfather, gave my mother this name, wild swans.

Annoushka Ducas:

Oh really?

Jung Chang:

And then when I was born, my step grandfather said, "Another wild swan is born."

Annoushka Ducas:

It's a wonderful name and clearly, you come from a very strong line of women. But one of the things I wanted to find out from you is, when did you decide or know that you wanted to write?

Jung Chang:

I always loved writing when I was a child. But when I was growing up in China in the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, it was impossible even to dream of becoming a writer because in those years, during Mao's incessant political persecutions, nearly all writers were condemned, sent to the gulag, driven to suicide to some or even executed. Even writing for oneself was dangerous. I wrote my first poem on my 16th birthday in 1968. It was in the middle of the culture revolution when books were burned across China. I was lying in bed polishing my poem when I heard the door banging. The Red Guard had come to raid our flat. If they saw my poem, I would get into trouble, my family would get into trouble so I had to quickly rush to the bathroom to tear up my poem and flush it down the toilet, and that ended my first venture in writing.

Annoushka Ducas:

Just going back on that, but you did so many things from being a bath doctor to electrician to steelwork. But do you always think that writing was in your soul?

Jung Chang:

Well, it was a urge, it was a passion, a urge you couldn't control and you couldn't vanish from your head. And when I was working as a peasant, when I was spreading manure in the paddy fields and when I was checking electricity supplies on top of the electricity post as an electrician, I was always writing in my head with an imaginary pen. I was always writing but I couldn't put pen to paper, and then I came to Britain in 1978 after Mao died in 1976 and the culture revolution ended. Now in Britain I could write but at that moment, the desire to write left me because I had come to a complete different world. It was like landing on Mars. Everything was exciting, everything was new and I just wanted to spend every minute absorbing this new world and to write for me would be to look backward and inward into a world I wanted to forget all about.

Jung Chang:

So I didn't want to write for 10 years. And then in 1988, my mother came to stay with me. For the first time, she told me the stories of her life and stories of my grandmother, her relationship with my father, and when she started, she couldn't stop and she stayed with me for six months. She talked everyday. When I was out working, she talked into a tape recorder and after she left, I wrote Wild Swans and I became a writer.

Annoushka Ducas:

And Jung, did you find it very painful writing it or was it a very cathartic experience? How did you find it?

Jung Chang:

I think it was both. On the one hand it was very painful because I had to recall particularly my father's been driven insane in the culture revolution and my grandmother's very painful death, and it was very painful but actually, it changed the pain. Writing enabled me to turn trauma into a form that you can record, into memory. So I'm actually very lucky because I wrote Wild Swans and I can now talk to you about my past without too much pain, and this is a luxury a lot of people don't have in China because they're not allowed to talk about the past and as a result, the trauma has been suppressed. So writing Wild Swans has done me tremendous good not to mention that it has brought me closer with my mother.

Jung Chang:

My mother was very sweet before Wild Swans was published. Just when I was about to feel a bit anxious how the book would be received and so, my mother wrote me from China and said, "The book might not do well, people might not pay attention to it but I was not worry," because she could see that writing the book had brought us closer together, came to a new degree of understanding and indeed love. I mean, I felt that way too. And so, my mother said I had made her a happy woman and that was enough. So I was completely serene when the book was published. I was not thinking about whether it would be successful or not and, of course, as it happened, it was a success so that was quite wonderful.

Annoushka Ducas:

Your mother must be so proud. Just finishing on that briefly, are you able to go back, obviously, out of COVID in a normal... In what we don't... Necessarily, now is a normal world. So are you able to go back and see her?

Jung Chang:

No. Well, the thing is this. When my second book, a biography of Mao was published and I lost the freedom to travel to China and the regime tried to ban me from going to China. But thanks to the help from the British government, I was allowed to go to China for 15 days a year, just to see my mother and that lasted for quite a few years. But at the moment, China is going backward. It's becoming more repressive at anytime since Mao's death and so, going to China, a lot of people say, had become very dangerous.

Annoushka Ducas:

Yes.

Jung Chang:

So I don't know whether I would see my mother again.

Annoushka Ducas:

Oh my.

Jung Chang:

My mother is coming up to 90 now and her head is still ultra clear. I mean, it's absolutely wonderful because at that age she's still a tower of strength for me and she and I have long realized that this is the price we have to pay for me to write books honestly.

Annoushka Ducas:

Yes.

Jung Chang:

I mean, sadly, probably very unlikely I would see my mother again.

Annoushka Ducas:

Your next

is a window box and you said it's a window box with brightly colored flowers. You could see I've drawn it as an arched window because it's soft and feminine and the flowers are all different shades of pink

And I'd see it in yellow gold and the window is white sapphire so it feels really precious. I'd love the idea of this window box and I'm dying to know why you chose a window box.

Jung Chang:

Well, window box is where the things I wrote back home about in my first letter after I came to London in 1978. And en route from Heathrow when we saw houses, I noticed the window boxes. I was so excited and they seem so beautiful. I mean, as beautiful as your drawing to me then. Because in China you know how crazy Mao was. He even condemned horticulture. He said, cultivating flowers and the grass was a bourgeois habit. Get rid of the gardeners. So when we were children, we had to go out of the classroom to remove grass from the school lawn and I saw flowers disappear from our homes, the vases smashed and no flowers. So then suddenly I saw these window boxes and I was in seventh heaven and so, that was all I wrote home about.

Annoushka Ducas:

It's so interesting that's what you noticed on your way from the airport. I love that because in your books, you have this ability to really make things very vivid for the readers, just wonderful.

Jung Chang:

Well, I think, yes. I think to notice this life's little pleasures, signs of beauty, it makes life worth living.

Annoushka Ducas:

And out of interest, are you a gardener? Do you love your garden or window?

Jung Chang:

I love my garden.

Annoushka Ducas:

Do you have window boxes where you are?

Jung Chang:

Not exactly window boxes but an expanded version of window box which is a balcony. I love our balcony, of course, and we have a very nice garden where I planted all sorts of things including lots of bamboo because I came from the place where there were hundreds of species of bamboo. There was a place called the bamboo forest and that's where I was born and so, I'd love that. In our balcony, I was particularly fond of our lemon tree and I just counted this morning, it had 24 lemons.

Annoushka Ducas:

Oh my goodness. Congratulations.

Jung Chang:

Yes. I love that. I mean, they gave me tremendous pleasure, these plants. I love gardens.

Annoushka Ducas:

Your next

is a globe which is music to my ears because, in fact, I wear this globe. Everyday, I wear this globe. And so, the globe I've drawn for you is it's completely round, I seen it as the sea being lapis, of lapis lazuli and then the continents in yellow gold. And if this was a

that you're going to choose, we probably put a little ruby in the particular place you found was special for you. It's set in a frame which has got

all the way around the frame. It's similar to the one I've got. And the idea is that you can spin it really, really fast and it becomes a worry bead for you. But I know why you chose this

I think you chose this charm because it represents your travel around the world. Tell me, because I think a lot of it is you traveled with Jon, your husband?

Jung Chang:

Yes. Yes. After Wild Swans was published, I was thinking about writing another book and then Mao seemed to be the obvious subject because he dominated my early life, and then he turned the lives of a quarter of the world's population upside down. And my husband, Jon, Jon Halliday, is also interested in Mao so we decided to embark on this project together. We actually divided our research by language. I dealt with the Chinese language resources and Jon, well, unfortunately, speaks many languages so he was landed with the rest of the world. And then he learned Russian when he was in Ireland when he was a child and that was really useful because we spent a lot of time working in the Russian archives.

Jung Chang:

So if you can put any thoughts perhaps Moscow is a place because in the 1990s we're very lucky, Yeltsin opened the archives of the Old Soviet Union and that was a treasure trove. And we found so many things about Mao, about the communist world and we just had a riveting time, and we also traveled all over the world and he interviewed almost everyone who had the interesting dealings with Mao. I mean, one particular person we interviewed was Imelda Marcos. Do you remember this woman,-

Annoushka Ducas:

Oh my goodness. Yeah. With all her shoes.

Jung Chang:

... a Filipino, and in her flat she had this little shoes, bejeweled little shoes dotted around her apartment so she had a kind of sense of humor. She had a very flirtatious relationship with Mao because Mao was a womanizer and when he met Imelda Marcos, the former Filipino beauty queen, Mao's eyes sparkled. He was nearly blind at that time but his eyes sparkled and he picked up Imelda's hand and kissed it. And this was such an incredible scene for us living in China at that time in 1974 because at that time, in the culture revolution, anyone who had showed any sign of gallantry, so to speak, would be condemned as bourgeois and being subject to denunciation meetings. But we saw this in the news reel in China.

Jung Chang:

I remembered the shock at that time. In fact, Mao's photographer was shocked and he didn't dare to take a photograph, but the news reel camera was fixed and kept rolling and recorded this moment and so we have a picture of that in Mao biography. And Imelda, when we interviewed her, she batted her eyelids furiously at Jon and then she turned to me and said, "Western men simply don't understand us Eastern women," and Jon said, "Have you come across any Western men who understand you?" She said, "Only one person, Richard Nixon." Well, she did have this relationship with Richard Nixon and before Mao died, the person Mao most wanted to see was Richard Nixon.

Annoushka Ducas:

Really?

Jung Chang:

And so, he kept inviting Richard Nixon to China and he sent Imelda Marcos to America to invite Nixon.

Annoushka Ducas:

That's cool. And Jung, and how did you meet Jon?

Jung Chang:

We met in London. I think at that time I was working in the 1980s. I was working for television series about China and Jon was making a series on the Korean War and we were introduced. I mean, Jon thought I could open doors for him in China and, of course, I did nothing of the kind. But we, let's say, fell in love and we got together.

Annoushka Ducas:

And was it love at first sight?

Jung Chang:

It wasn't.

Annoushka Ducas:

It wasn't.

Jung Chang:

But it was pretty soon after that.

Annoushka Ducas:

I mean, as you said, you said what? Ten or 12 years traveling the world to write the book about Mao. I mean, that's a quite an intense relationship to have.

Jung Chang:

Yes. Yes, absolutely. We spent 12 years writing this biography of Mao. For 12 years, we were together all the time and we travel the world, we did research in the archives, and in London, at home, we worked separate studies. And at lunch time, we were together exchanging our discoveries and often, even when we went out, we were talking to each other. I mean, we had a riveting time.

Annoushka Ducas:

What a team. But I guess difficult to draw a distinction between the life and work balance or the two are just so intertwined?

Jung Chang:

They were so intertwined. We had the most wonderful time. We were, I must say, the perfect team.

Annoushka Ducas:

Will you ever write another book together?

Jung Chang:

No. I think then Mao was where our interests overlapped then I started writing other Chinese figures, Jon was not that interested in. So I wrote a biography of Empress Dowager Cixi who was the last great royal ruler of China who brought medieval China into the modern age.

Annoushka Ducas:

And that brings us quite neatly onto your next charm which is the boat of purity and ease because I think that's very much part of why you've chosen that. I was just so struck by the fact that it's not actually a boat at all. It's a pavilion disguised to look like a boat-

Jung Chang:

Yes.

Annoushka Ducas:

... made of wood painted to look like marble. So I had seen it really as yellow gold with some tsavorite cabochons on the windows and I see it as a locket so the bottom will open and you'll be able to go inside it and look at the detail from the inside out. That's how I imagine it. Tell me more about why you've chosen this charm.

Jung Chang:

Well, it's a magnificent boat in the Summer Palace in Beijing, and the Empress Dowager Cixi was always accused of indulging herself in these luxuries at the cost of the country. And, of course, it's a complete myth and it wasn't true and this was relevant to my desire to write about her. Because gradually, from writing Wild Swans, I realized that the image we were taught from history books about the Empress Dowager was very, very different from the real woman.

Jung Chang:

The first thing that struck me was actually about foot binding and we, in China, were always taught, given the impression that foot binding was somehow banned by the communists. And then I suddenly realized when I was researching Wild Swans, it was the Empress Dowager who first banned foot binding and this was so different from her image of being this cruel woman who dragged China behind and who was responsible for all China's troubles. She has been maligned for hundred years and is still being maligned but, in fact, she was the first modernizer in China and she brought China into the modern age. She had been a low-level concubine to the emperor but after the emperor died, she launched the palace coup in 1861 and she's started to change China.

Jung Chang:

I mean, everything modern we have today, electricity in the modern whatever army, trade, diploma, say schools, language, women's liberation, everything had started with her. And also, when she started being the ruler of Chinese empire, she wasn't even allowed to be face to face with her male officials. She had to sit behind a screen. I mean, it was from that very constrained world and she changed China in a very non-violent way. I admire her very much through my research.

Annoushka Ducas:

What do you think the position of women in China is today out of interest? Where do women stand in China today?

Jung Chang:

Well, starting from her, I mean, women's liberation has really taken off in China and has in many ways women's positions have improved tremendously. But, of course, I mean, in terms of politics, there is still no women in Mainland China's political lineup and one reason was that I would like to think that it actually speaks well of women because you need a certain killer instinct to get on top in that communist party system. And women are basically unsuited but I think this is to women's credit.

Annoushka Ducas:

Just finishing on that, do you think that women are treated equally to men not in politics but in other walks of life now in China?

Jung Chang:

I think, yes. I think, yes. I think now perhaps the suppression of women is not so much institutional but from older prejudices. When I was a child in China I heard the saying that women have long hair but short intelligence which later actually encouraged me to grow my hair very long. My hair is shorter now but until fairly recently, my hair reached my knee so it was going really overboard.

Annoushka Ducas:

So Jung, your last

this is completely fascinating to me when you told me about this, is a necklace around a mountain. Now, I actually think rather than me describe this

first because I think most people listen to this won't really be able to believe what it is. I'll describe it once we've discussed it, I think. But when you told me about it, I had to look it up because I didn't know anything about it. But I looked it on Google maps and I saw that it's just this vast piece of landscaping, an act of bending nature to human desires. I mean, extraordinary. But this necklace around a mountain, can you tell us about the story behind this?

Jung Chang:

Yes. Well, after Empress Dowager Cixi, I wrote a book which is my last book about the famous Chinese Soong sisters from Shanghai and the book is called Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister. Little Sister May-Ling was Madame Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang Kai-shek was the ruler of China before Mao defeated him and drove him to Taiwan. Now, Chiang Kai-shek had started his political career as an assassin and that's how he got on top. And as a result, he and May-Ling, his bride, were pursued by assassins and some even got into their bedroom and as a result, little sister May-Ling suffered a miscarriage and was never able to have children. Now, Chiang Kai-shek loved his wife and wanted to pull her out of depression. So in 1932, he gave her a necklace as a birthday present, but as you mentioned, it's no ordinary necklace because it encircled a whole mountain.

Jung Chang:

Now, what it is was he imported this French pine trees and planted them around this mountain like the chains of the necklace, and these French trees color in late autumn in the different way from the local Chinese trees. So they form a distinctive chain and the jewel of the necklace was a villa with beautiful green, blue roof which sparkle under the sun looking like a real jewel. So this palace was called the Meiling Palace because he dedicate it to his wife.

Annoushka Ducas:

I mean, it's so extraordinary. I'd encourage everybody to look it up. It feels so very Chinese to me and its scale and beauty and just the size of the gesture. Because my experience whenever I've been to China is that everything is massive. I just found it extraordinary. And I also found it extraordinary that it survived the culture revolution.

Jung Chang:

Well, the thing is, well, for many years, people didn't realize what it was because you need a private plane-

Annoushka Ducas:

Yes.

Jung Chang:

... to fly over it, to enjoy it. I mean, of course, Chiang Kai-shek could fly his wife to see it but nobody was allowed to fly over that mountain until fairly recently. I think a film crew or something, I mean, with permission accidentally discovered it.

Annoushka Ducas:

Yes.

Jung Chang:

And then, of course, from the archives, documents were dug out and the whole history of this extraordinary necklace came to light.

Annoushka Ducas:

It's absolutely incredible. I mean, I had seen it as a circle of tsavorite cabochons representing the color of those trees that are the necklace. And then, inside to have the palace, as you say, with this different color greeny blue tiles on the roof. I've used fluorite to do that because they are very soft-colored stone that catch the light different ways and satin yellow gold.

Annoushka Ducas:

I mean, one of my questions is, you've lived here now for over 40 years, I think, and I wonder you've written so much it's been your life writing about China. How connected do you feel to China now?

Jung Chang:

Well, I feel, I mean, connected in a sense that I'm interested. I mean, I care about the place, I care about the people. I feel they've been through so much and really deserve some good life. And my mother lives there, as I said. She's nearly 90 and I have a sister there, I have a brother who live there. I mean, I'm very sad that it seemed to be, politically, seem to be turning backwards.

Annoushka Ducas:

You feel it's turning backwards.

Jung Chang:

I've just feel very, very sad about that.

Annoushka Ducas:

Do you see your sister or your brother at all?

Jung Chang:

Well, I haven't seen them for some time but, again, Skype.

Annoushka Ducas:

Skype.

Jung Chang:

I mean, modern technology.

Annoushka Ducas:

Yes. Yes.

Jung Chang:

Actually, it makes the meetings quite real. I talk to my sister every other day. What I can say is that I see them and we talk and I don't feel I'm cut off from them.

Annoushka Ducas:

Right. Yes. How wonderful.

Jung Chang:

We are a very close family and the culture revolution has wrecked many families because wives or spouses were encouraged or forced to denounce each other and children set to pang their parents. But my family grew closer and that makes me very happy.

Annoushka Ducas:

Well, as you say, very lucky to have these wild swans that you were and are.

Jung Chang:

Absolutely wonderful idea. Thank you.

Annoushka Ducas:

Thank you so much. What an absolutely fascinating story to hear about all of these

But as a thank you for all your time, I would love to make you one of these charms, and I'd love you to tell me which one you would like. And whilst you're thinking about that, when somebody in the future finds this charm bracelet, I just wonder what you would like this

to say about you. What would be the legacy that somebody finding this bracelet, maybe one of your nephews or nieces, what would you like it to say about you?

Jung Chang:

Well, perhaps, I think in life I like to feel that I have the priority right and I feel that love and affection and family... I mean, those things are very important to me. I mean, I think I guess I'm brought up by my grandmother who always said, "If you have love, plain cold water is sweet," and I guess I feel that it's the most important thing in life.

Annoushka Ducas:

Absolutely right. And so, which

would you like me to make you?

Jung Chang:

Well, I think maybe the cogon grass because that's the image of my mother running towards me with the grass surging around her.

Annoushka Ducas:

Okay. I should really look forward to doing that and giving it to you when it's done.

Jung Chang:

Thank you. Thank you so much. Thank you very much.

Annoushka Ducas:

Thank you so much for listening to My Life in Seven Charms with me, Annoushka Ducas. Please do like, review, and subscribe to hear our latest episodes. Thank you to Fairly Media for our audio production.